By: Jack Dawson

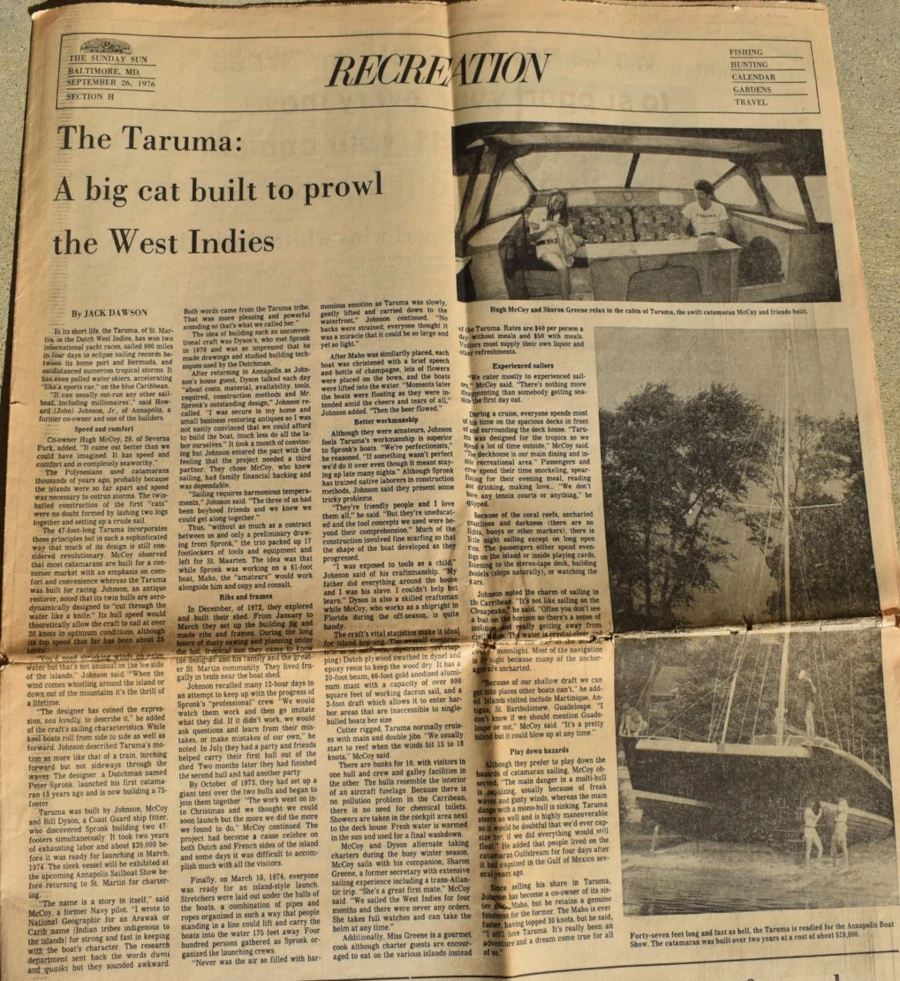

In its short life, the Taruma, of St. Martin in the Dutch West Indies, has won two international yacht races, sailed 900 miles in four days to eclipse sailing records between its home port and Bermuda, and outdistanced numerous tropical storms. It has even pulled water skiers, accelerating “like a sports car,” on the blue Caribbean. It can usually out-run any other sailboat, including millionaires’,” said Howard (John) Johnson, Jr., of Annapolis, a former co-owner and one of the builders.

Speed and comfort

Co-owner Hugh McCoy, 29, of Severna Park, added, “It came out better than we could have imagined. It has speed and comfort and is completely seaworthy.”

The Polynesians used catamarans thousands of years ago. Probably because the islands were so far apart and speed was necessary to outrun storms. The twin-hulled construction of the first “cats” were no doubt formed by lashing two logs together and setting up a crude sail.

The 47-foot-long Taruma incorporates those principles but in such a sophisticated way that much of its design is still considered revolutionary. McCoy observed that most catamarans are built for a consumer market with an emphasis on comfort and convenience whereas the Taruma was built for racing. Johnson, an antique restorer, noted that its twin hulls are aerodynamically designed to “cut through the water like a knife.” Its hull speed would theoretically allow the craft to sail at over 30 knots in optimum conditions, although its top speed thus far about 25 knots.

“You’d need shrieking winds on calm water but that’s not unusual on the lee side of the islands,” Johnson said. “When the wind comes whistling around the island or down out of the mountains it’s the thrill of a lifetime.”

The designer has coined the expression, sea kindly, to describe it,” he added of the craft’s sailing characteristics. While keel boats roll from side to side as well as forward, Johnson described Taruma’s motion as more like that of a train, lurching forward but not sideways through the waves. The designer, a Dutchman, named Peter Spronk, launched his first catamaran 13 years ago and is now building a 75 footer.

Taruma was built by Johnson, McCoy and Bill Dyson, a Coast Guard ship fitter, who discovered Spronk building two 47-footers simultaneously. It took two years of exhausting labor and about $20,000 before it was ready for launching in March, 1974. The sleek vessel will be exhibited at the upcoming Annapolis Sailboat Show before returning to St. Martin for chartering.

“The name is a story in itself,” said McCoy, a former Navy pilot. “I wrote to National Geographic for a Arawak or Carib name [Indian tribes indigenous to the islands] for strong and fast in keeping with the boat’s character. The research department sent back the words dumi and quaiki but they sounded awkward. Both words came from the Taruma tribe. That was more pleasing and powerful sounding so that’s what we called her.”

The idea of building such an unconventional craft was Dyson’s, who met Spronk in 1970 and was so impressed that he made drawings and studied building techniques used by the Dutchman.

After returning to Annapolis as Johnson’s house guest, Dyson talked each day “about costs, material, availability, tools required, construction methods and Mr. Spronk’s outstanding design,” Johnson recalled. “I was secure in my home and small business restoring antiques so I was not easily convinced that we could afford to build the boat, much less do all the labor ourselves.” It took a month of convincing but Johnson entered the pact with the feeling that the project needed a third partner. They chose McCoy, who knew sailing, had family financial backing and was dependable.

“Sailing requires harmonious temperaments,” Johnson said. “The three of us had been boyhood friends and we knew we could get along together.”

Thus, “without as much as a contract between us and only a preliminary drawing from Spronk,” the trio packed up 17 footlockers of tools and equipment and left for St. Maarten. The idea was that while Spronk was working on a 61-foot boat, Maho, the “amateurs” would work alongside him and copy and consult.

Ribs and frames

In December, of 1972, they explored and built their shed. From January to March they set up the building jig and made ribs and frames. During the long hours for the dusty sawing and planning under the hot, tropical sun they came to know the designer and his family and the greater St. Martin community. They lived frugally in tents near the boat shed.

Johnson recalled many 12-hour days in an attempt to keep up with the progress of Spronk’s “professional” crew “we would watch them work and then go imitate what they did. If it didn’t work, we would ask questions and learn from their mistakes, or make mistakes of our own,” he noted. In July they had a party and friends helped carry their first hull out of the shed. Two months later they had finished the second hull and had another party.

By October of 1973, they had set up a giant tent over the two hulls and began to join them together. “The work went on into Christmas and we thought we could soon launch but the more we did the more we found to do,” McCoy continued. The project had become a cause celebre on both Dutch and French sides of the island and some days it was difficult to accomplish much with all the visitors.

Finally, on March 10, 1974, everyone was ready for an island-style launch. Stretchers were laid out uner the hulls of the boats, a combination of pipes and ropes organized in such a way that people standing in a line could lift and carry the boats into the water 175 feet away. Four hundred persons gathered as Spronk organized the launching crews.

“Never was the air so filled with harmonious emotion as Taruma was slowly, gently lifted and carried down to the waterfront,” Johnson continued. “No backs were strained; everyone thought it was a miracle that it could be so large and yet so light.”

After Maho was similarly placed, each boat was christened with a brief speech and bottle of champagne, leis of flowers were placed on the bows, and the boats were lifted into the water. “Moments later the boats ere floating as they were intended amid the cheers and tears of all,” Johnson added. “Then the beer flowed”

Better workmanship

Although they were amateurs, Johnson feels Taruma’s workmanship is superior to Spronk’s boats. “We’re perfectionists,” he reasoned. “If something wasn’t perfect we’d do it over even though it meant staying up late many nights.” Although Spronk has trained native laborers in construction methods, Johnson said they present some tricky problems.

“They’re friendly people and I love them all,” he said. “But they’re uneducated and the tool concepts we used were beyond their comprehension.” Much of the construction involved fine scarfing so that the shape of the boat developed as they progressed.

“I was exposed to tools as a child,” Johnson said of this craftsmanship. “My father did everything around the house and I was his slave. I couldn’t help but learn.” Dyson is also a skilled craftsman while McCoy, who works as a shipright in Florida during the off-season, is quite handy.

The craft’s vital statistics make it ideal for island hopping. The overall construction is of half-inch, lapstraked (overlapping) Dutch plywood swathed in dynel and epoxy resin to deep the wood dry. It has a 20-foot beam, 46-foot gold anodized aluminum mast with a capacity of over 800 square feet of working dacron sail, and a 2-foot draft which allows it to enter harbor areas that are inaccessible to single-hulled boats her size.

Cutter rigged, Taruma normally cruises with main and double jibs. “We usually start to reef when the winds hit 15 to 18 knots,” McCoy said.

There are bunks for 10, with visitors in one hull and crew and galley facilities in the other. The hulls resemble the interior of an aircraft fuselage. Because there is no pollution problem in the Caribbean,

There is no need for chemical toilets. Showers are taken in the cockpit area next to the deck house. Fresh water is warmed in the sun and used for a final washdown.

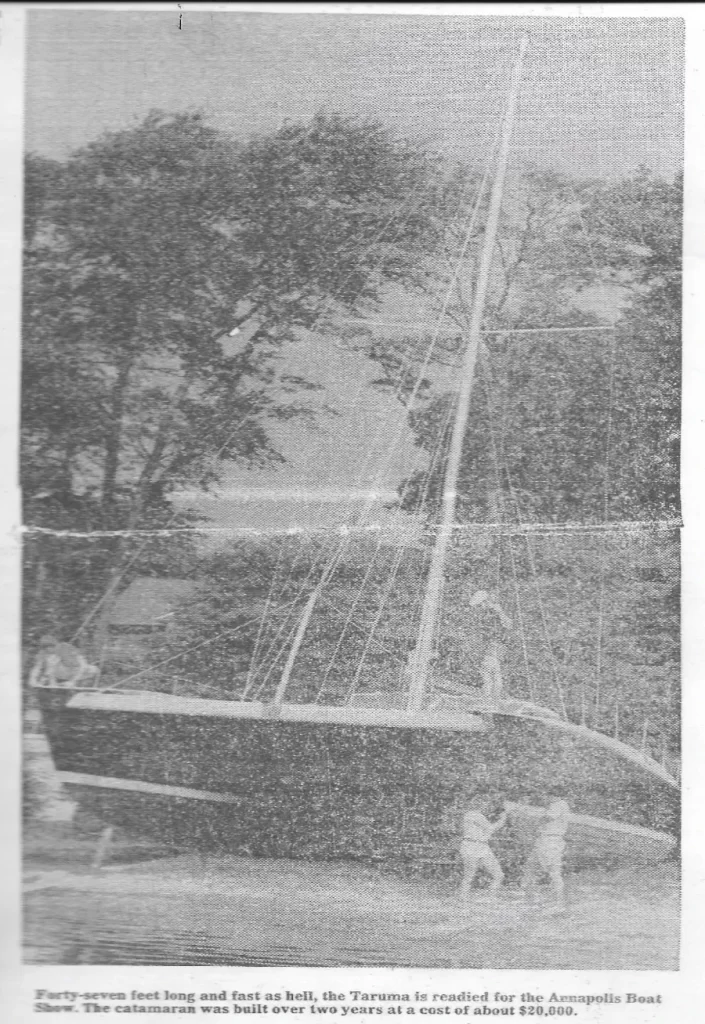

McCoy and Dyson alternate taking charters during the busy winter season. McCoy sails with his companion, Sharon Greene, a former secretary with extensive sailing experience including a trans-Atlantic trip. “She’s a great first mate,” McCoy said. “We sailed the West Indies for four months and there were never any orders. She takes full watches and can take the helm at any time.”

Additionally, Miss Greene is a gourmet cook although charter guests are encouraged to eat on the various islands instead of the Taruma. Rates are $40 per person a day without meals and $50 with meals. Visitors must supply their own liquor and other refreshments.

Experienced sailors

“We cater mostly to experienced sailors,” McCoy said. “There’s nothing more disappointing than somebody getting seasick the first day out.”

During a cruise, everyone spends most of his time on the spacious decks in front of the surrounding the deck house. “Taruma was designed for the tropics so we spend a lot of time outside,” McCoy said. “The deckhouse is our main dining and inside recreational area.” Passengers and crew spend their time snorkeling, spearfishing for their evening meal, reading and drinking, making love…. “We don’t have any tennis courts or anything,” he quipped.

Because of the coral reefs, uncharted coastlines and darkness (there are no lights, buoys or other markers), there is little night sailing except on long open runs. The passenger either spend evenings on the island or inside playing cards, listening to the stereo-tape deck, building models (ships naturally), or watching the stars.

Johnson noted the charm of sailing in the Caribbean. “It’s not like sailing on the Chesapeake,” he said. “Often you don’t see a boat on the horizon so there is a sense of isolation and really getting away from civilization. The water is crystal clear and you can see all the way to the bottom even by moonlight. Most of the navigation is by sight because many of the anchorages are uncharted. “Because of our shallow draft we can get into places other boats can’t,” he added. Islands visited include Martinique, Antigua, St. Bartholomew, and Guadeloupe. “I don’t know if we should mention Guadeloupe or not,” McCoy said. “It’s a pretty island but it could blow up at any time.

Play down hazards

Although they prefer to play down the hazards of catamaran sailing, McCoy observed, “The main danger in a multi-hull is capsizing, usually because of freak waves and gusty winds, whereas the main danger with a mono-hull is sinking. Taruma steers so well and is highly maneuverable so it would be doubtful that we’d ever capsize but if we did everything would still float.” He added that people lived on the catamaran Gulfstream for four days after it had capsized in the Gulf of Mexico several years ago.

Since selling his share in Taruma, Johnson has become a wo-owner of its sister ship, Maho, but he retains a genuine fondness for the former. The Maho is ever faster, having topped 30 knots, but he said, “I still love Taruma. It’s really been an adventure and a dream come true for all of us.”

Be the first to comment